88 per cent of organisations now use artificial intelligence in at least one business function, but only a third have scaled it beyond pilots (McKinsey, 2025). Across the fifty-plus companies we’ve supported, the pattern is identical on a smaller scale: AI experiments that look brilliant in demos fail when they meet production reality. The cause isn’t lack of talent or curiosity. It’s weak architecture.

In marketing analytics this failure is acute. Teams grant a large language model access to the warehouse, type a natural-language question, and watch it generate a confident but incorrect SQL query. The chart looks plausible, yet the joins are wrong, conversions are double-counted, and the result collapses under scrutiny. The problem isn’t the model’s intelligence — it’s that the system has no structure.

McKinsey’s State of AI in 2025 report highlights this gulf between experimentation and impact. Sixty-two per cent of organisations are already experimenting with AI agents, but only twenty-three per cent have scaled them in any function. The small group of “AI high performers” — roughly six per cent of global respondents — are three times more likely to redesign workflows before they automate them and five times more likely to commit over 20 per cent of digital budgets to AI. They treat automation as engineering, not experimentation.

That distinction defines Tasman’s perspective. From our experience delivering analytics for fast-growing companies such as PensionBee, Kaia and Peak, genuine business value emerges only when AI behaves like software: modular, versioned, and testable. We call this agentic analytics — a new layer of the modern data stack where small, specialised agents perform one well-defined task, producing outputs that can be traced, tested, and improved.

How Analytics Lost Its Discipline

Since 2023, the analytics industry has moved at AI speed. Every few months a new “data co-pilot” promised to make dashboards obsolete. In reality, most of those systems hit the same wall: some correct answers (when bounded) but a whole lot of hallucinations. The rather infamous MIT-Sloan study this spring found that 95 per cent of enterprise AI pilots failed to show measurable P&L impact (MIT Sloan, 2025).

This is a familiar cycle. In 1990, economist Paul David described the ‘dynamo paradox’: factories installed electric motors decades before productivity rose because workflows stayed the same. Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm later applied the same logic to technology adoption. AI analytics now sits squarely in that trough. Hype has peaked; discipline must follow.

At Tasman we see two recurring failure patterns. The first is speed without semantics — teams move fast but never define what “revenue” or “conversion” means. The second is automation without accountability — prompts generate SQL that no one reviews. Both patterns can be fixed, but not by larger models. They require software-like thinking: interfaces, contracts, and tests.

Just like there’s a difference between coding and software engineering, there is a major difference between an AI demo and an actual production system.

Defining Agentic Analytics

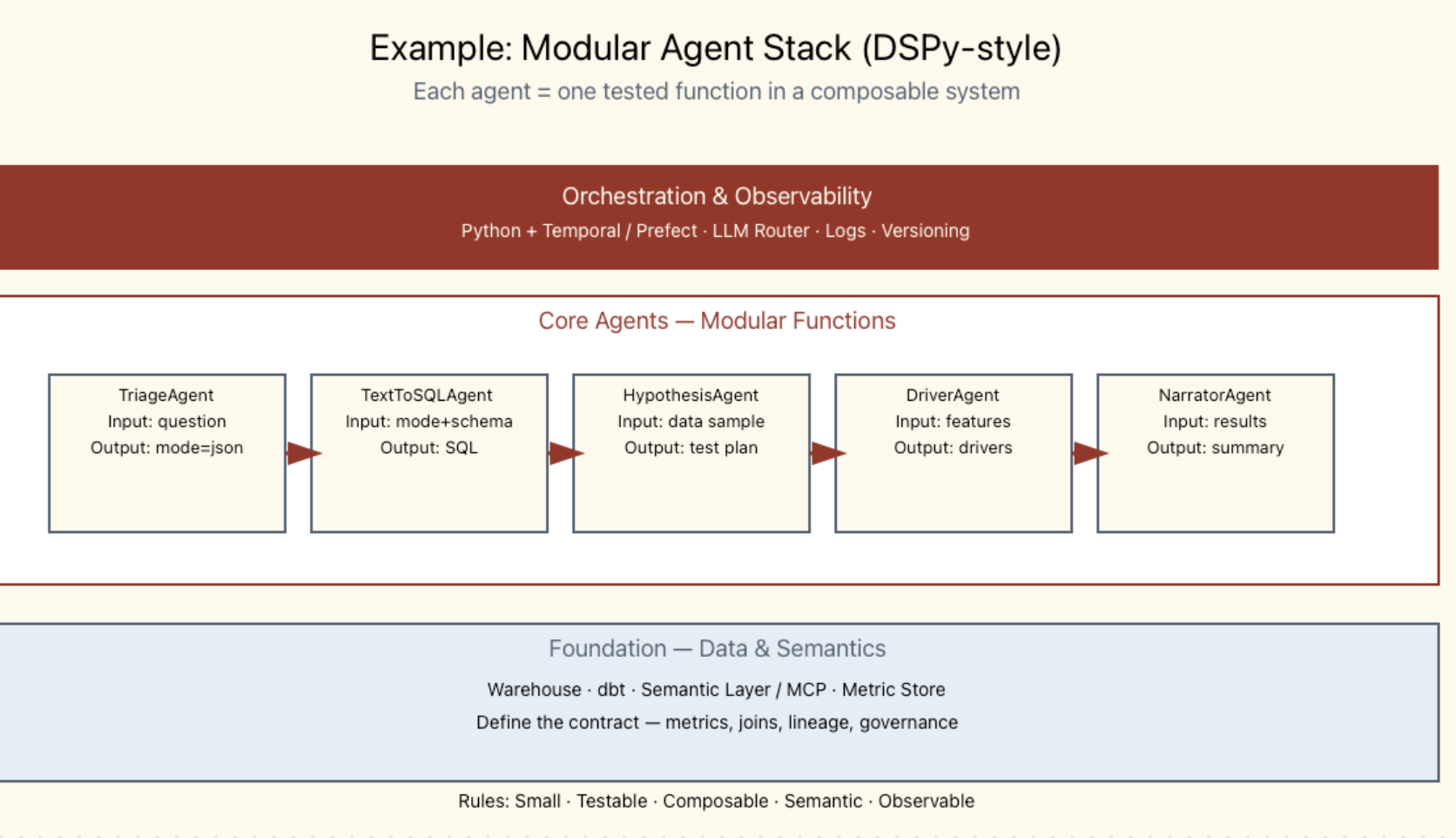

Agentic analytics isn’t a new tool. It’s a new architecture. Instead of a monolithic AI trying to interpret a question end-to-end, it breaks the process into modular steps handled by individual agents — each with a single responsibility and a clear input/output contract.

- TriageAgent determines whether the request is a simple search or a deeper analysis.

- TextToSemanticAgent converts a natural-language question into a validated semantic query (e.g.

cac_by_channelover 90 days). - MetricRunner compiles that semantic request into safe SQL, using only approved joins and metric definitions.

- HypothesisAgent tests a specific change — for example, what happens if five per cent of budget shifts from Facebook to LinkedIn.

- NarratorAgent summarises results, limitations, and next actions.

Each agent is independently testable and observable. Inputs, outputs, and versions are logged. Together, they form a reliable reasoning chain.

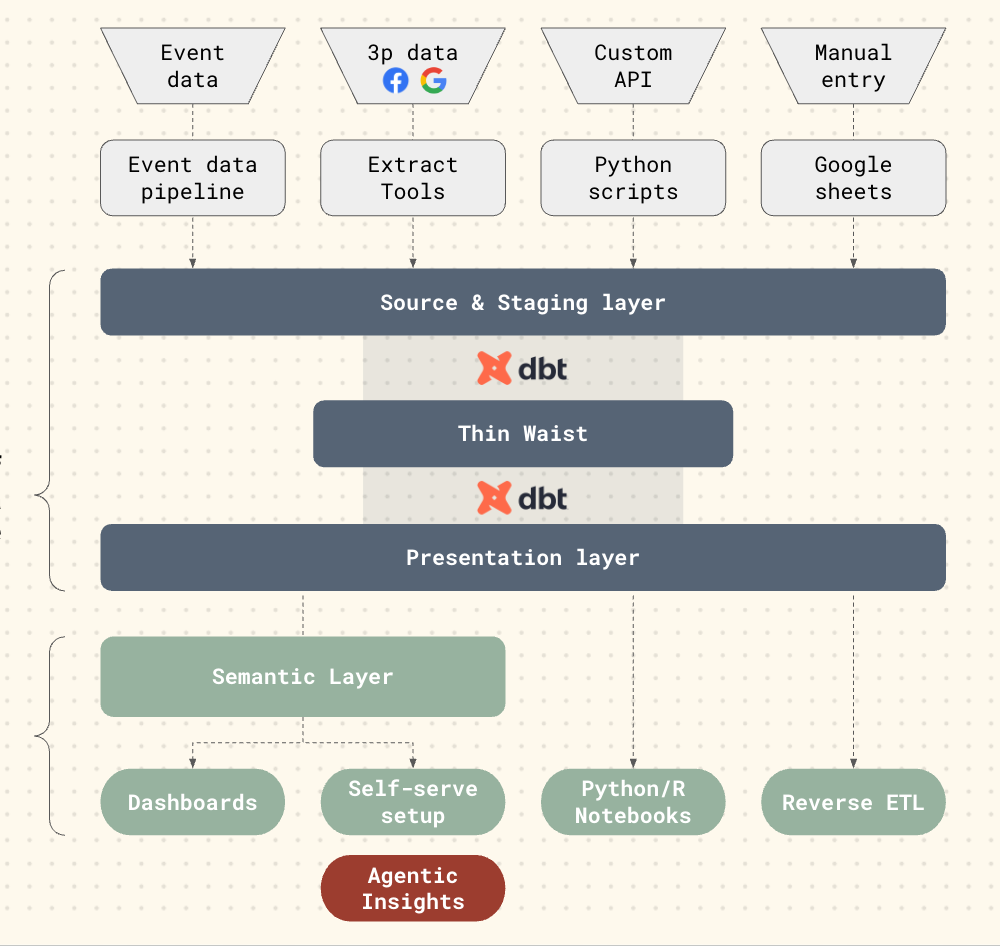

Warehouse → dbt Models → Semantic Layer → Agent Layer → Dashboard

Principle: LLMs consume from the presentation layer, never from raw data.

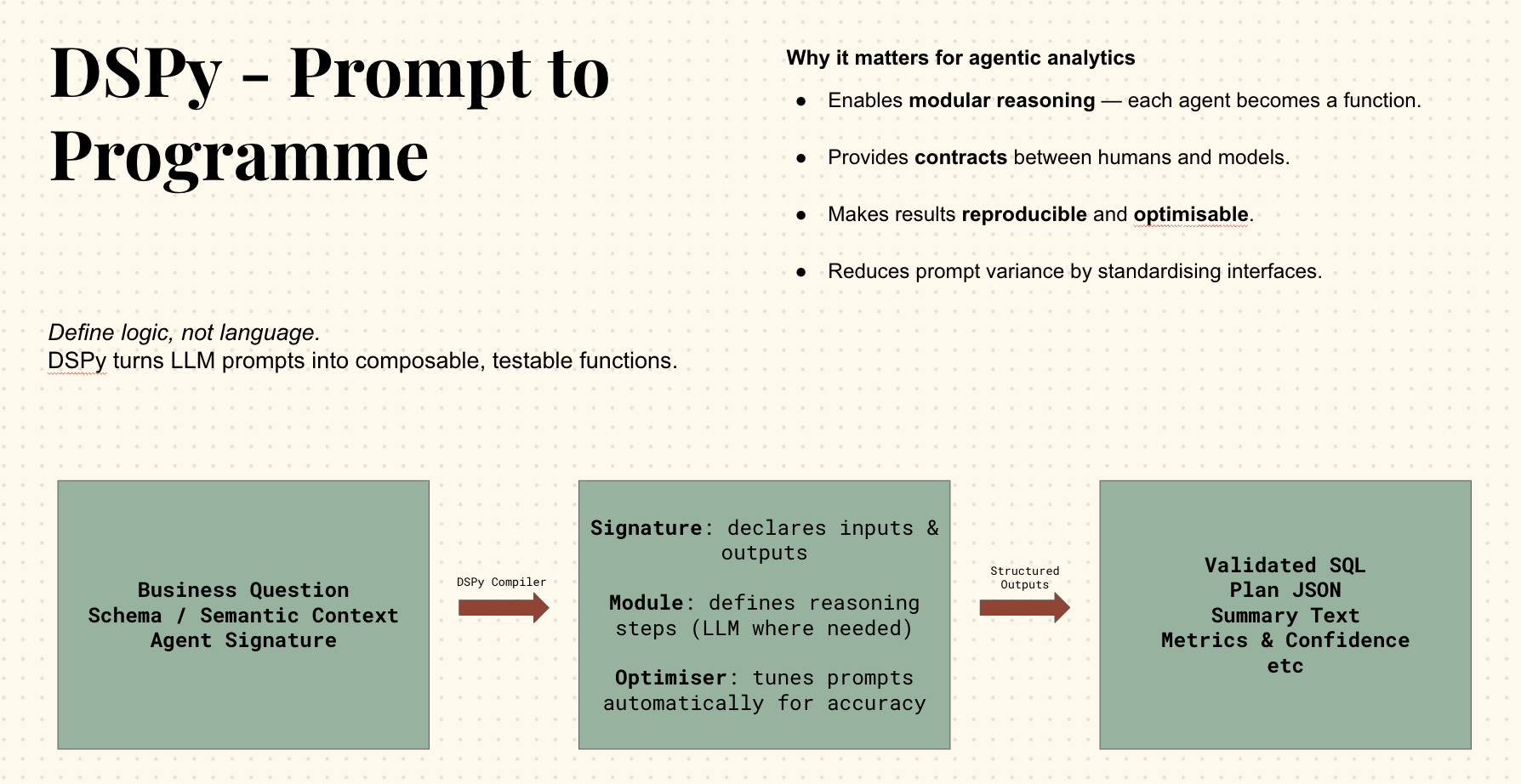

The agentic design is modular as well and is inspired by Stanford’s DSPy framework, which treats large language models as composable functions with explicit signatures. Rather than writing opaque prompts, you define interfaces — clear expectations for what the model receives and what it must return. The framework then automatically builds, tunes, and tests those prompts in the background, much like a compiler optimising code. The principle is simple but transformative: agents stop being improvisers and start behaving like software components.

For analytics, this approach solves two long-standing problems. First, it enforces separation of concerns — a Text-to-SQL agent doesn’t try to explain results, and a Narrator agent never touches data. Second, it enables reproducibility: each signature is versioned, benchmarked, and measurable. In our own tests, applying DSPy-style signatures to marketing datasets reduced prompt variability by over 80 per cent, turning what had been heuristic workflows into deterministic ones. The result is an analytics system that can evolve safely — adding new agents without breaking old ones, improving reasoning where human input is thin, and keeping statistical and semantic correctness exactly where it belongs.

The Semantic Layer: The Hidden Contract

Every reliable agentic system rests on a strong semantic layer — the dictionary of metrics, joins, and entities that define the truth. Without it, even the best prompt has nothing to anchor to.

In practice, this means implementing a metric store such as dbt’s Semantic Layer or Omni’s AI Assistant, which exposes metrics to agents via governed APIs.

At the enterprise end, Treasure Data’s AI Marketing Cloud demonstrates the principle at scale. Its micro-agents compress campaign planning from 8–12 weeks to one week by chaining four specialised steps: Target discovery → Root-cause analysis → Hypothesis generation → Experiment design. Results are reproducible because each stage references a defined dataset.

For lean teams, the same pattern works with a DuckDB file and a YAML schema. Define metrics once (spend, impressions, clicks, revenue, cac, roas) and forbid agents from inventing new ones. This small constraint eliminates most analytical hallucinations we see in LLM-generated SQL.

Hypothesis Testing: Guardrails for Insight

Hypothesis testing is the anchor of disciplined analytics. It transforms open-ended exploration into structured inquiry, forcing every claim to meet a standard of evidence. In practice, this means defining a clear statement that can be proven wrong — for instance, “LinkedIn campaigns deliver higher CTR than Facebook over the past 90 days” rather than “Find insights in paid social.” The difference seems semantic, but it determines whether the analysis produces knowledge or noise. Agentic systems that skip this step drift quickly into what McKinsey calls “false precision” — confident answers without statistical grounding.

In our architecture, hypothesis testing isn’t an afterthought; it’s encoded as a workflow. The Hypothesis Agent defines comparison groups, selects the appropriate statistical test, and records its confidence interval, effect size, and assumptions. This makes each result reproducible and falsifiable, a necessity also emphasised in guidance from the Royal Statistical Society. In our client work, teams that apply this method typically cut redundant re-analysis by more than half because every insight carries a testable trail — SQL, metric definition, and statistical output — not just a narrative.

Two Demos

Question: “Which channel mix change is most likely to improve CAC next month, given a recent anomaly in referral traffic?”

Demo 1 – The One-Shot Agent

The LLM generated SQL over the full warehouse. The result looked convincing but was wrong: it joined fact_orders directly to dim_campaigns, inflating revenue by 200 per cent, ignored date windows, and used orders instead of conversions for CAC.

Demo 2 – The Modular Stack

Using DSPy-style agents, the triage module identified the query type, mapped it to a validated metric request (cac_by_channel over 90 days), enforced correct joins from YAML, and executed a statistical test. Each run logged JSON of inputs, SQL IDs, execution time, and outputs.

Check out the notebooks over here in our Github account: Marketing Agent Demo

One is plausible theatre; the other is science.

Evidence from the Field

McKinsey reports that AI high performers are three times more likely to redesign workflows and five times more likely to commit over 20 per cent of digital budgets to AI (McKinsey, 2025).

Treasure Data’s AI agents increased campaign velocity eightfold. Omni’s semantic layer reduced reporting errors to zero (dbt documentation). We see similar gains when teams adopt a “define-once, automate-many” model.

Build or Buy? Be Pragmatic

Startups often ask whether to build or buy. The practical answer: buy plumbing, build logic.

Use off-the-shelf tools for ingestion, storage, and orchestration — Snowflake or DuckDB, dbt for modelling, Prefect or Temporal for scheduling. Then build the agentic layer yourself. A few Python modules and a YAML file can deliver measurable gains in reliability and transparency.

We’ve implemented this for teams of two analysts. The benefit isn’t speed — it’s repeatability.

The next stage won’t be larger models but shared standards. The Model Context Protocol now links LLMs directly to data semantics. Projects such as DSPy and RAG-based frameworks like Ragstar are formalising how agents reason together.

Closing Thought

Most AI analytics failures aren’t conceptual; they’re procedural. Teams skip the semantic groundwork, treat LLMs as oracles, and wonder why results vary day to day. The fix is dull but powerful: structure.

Agentic analytics is simply software engineering applied to reasoning. Small, sharp agents. Big, boring reliability.