SQL has come a long way since it was first introduced in the 1970s. As of 2026, there are now over 160 relational databases (according to DB-Engines), with SQL being the third most popular language used by developers (according to the 2025 Stack Overflow Developer Survey).

We’ve seen 10 iterations of the SQL standard, but many of the relational database systems have implemented a huge variety of vendor-specific features in their SQL language.

Given how broad “SQL” is as a topic, our upcoming articles highlight some of the modern SQL features that we’ve come to love — and we’re sure that you’ll love, too!

Table of content

- Filter results with QUALIFY

- RANGE and GROUPS in windows

- EXCLUDE rows in a window frame

- NULL-safe comparison with IS [NOT] DISTINCT FROM

- Expressive join types

- Transpose tables with PIVOT and UNPIVOT (coming up in part 2)

- Advanced GROUP BY options (coming up in part 2)

- Simplified grouping with GROUP BY ALL (coming up in part 2)

- First-class support for compound data types (coming up in part 2)

- Recursive common table expressions (coming up in part 2)

This article starts with the first 5. Stay tuned for the second article covering the rest of the list!

1. Filter results with QUALIFY

This is easily one of the most popular clauses in modern SQL. The best way to think of QUALIFY is that QUALIFY is the window equivalent of HAVING. This means that a SQL query now has three places that it can apply filters (excluding inner joins):

WHERE: filters rows before any joins and calculationsHAVING: filters rows immediately after any aggregationsQUALIFY: filters rows immediately after any window expressions

A common pattern prior to QUALIFY was to use a window function in a CTE/subquery and filter on its result in a downstream WHERE clause. The QUALIFY clause means that we don’t need the CTE/subquery! For example, selecting the most recently updated customer records:

Without QUALIFY

|

With QUALIFY

|

Using QUALIFY is much cleaner!

The QUALIFY clause is available in many modern data platforms, such as:

2. RANGE and GROUPS in windows (not just ROWS!)

If you’ve ever bounded a window range, chances are you’ve only ever really used the ROWS frame type. For example, calculating a 7-day running total of sales:

select

sales_date,

sum(revenue) over (

order by sales_date

rows between 6 preceding and current row

) as seven_day_running_total

from sales

The ROWS frame type is intuitive, but it’s not always the most appropriate frame type to use. There are two more frame types, RANGE and GROUPS; simplified definitions of all three are:

ROWSkeeps surrounding rows by how many rows away they are from the current rowRANGEkeeps surrounding rows by their value difference relative to the current rowGROUPSkeeps surrounding rows by how many distinct values away they are from the current row

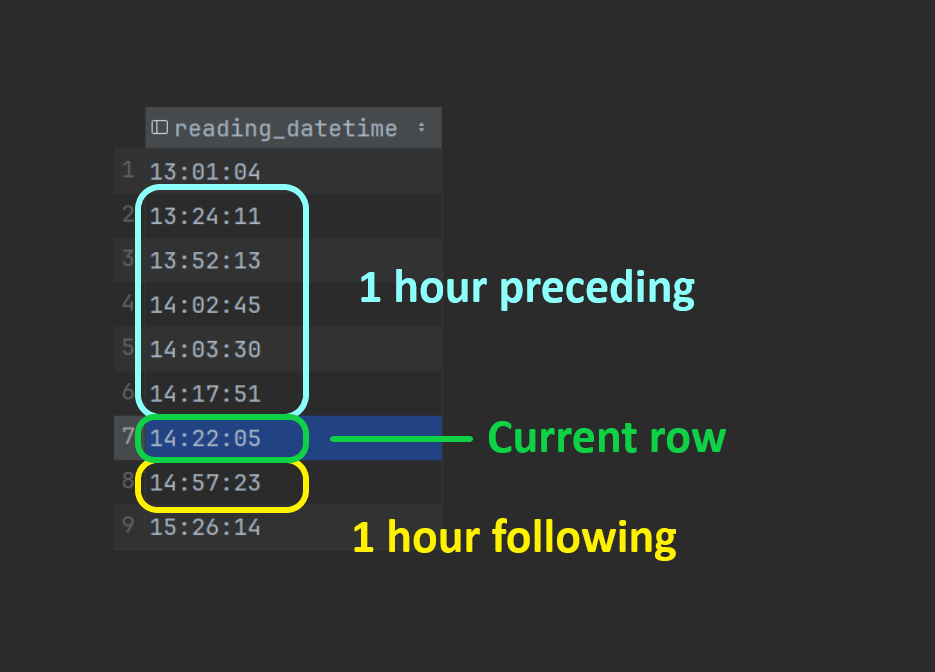

To help illustrate how RANGE and GROUPS work, the images below highlight which rows would be included in some example queries (DuckDB/PostgreSQL compatible syntax):

RANGE query

select

reading_datetime,

temperature,

avg(temperature) over (

order by reading_datetime

range between interval '1 hour' preceding

and interval '1 hour' following

) as avg_temperature_within_hour

from readings

RANGE selected rows

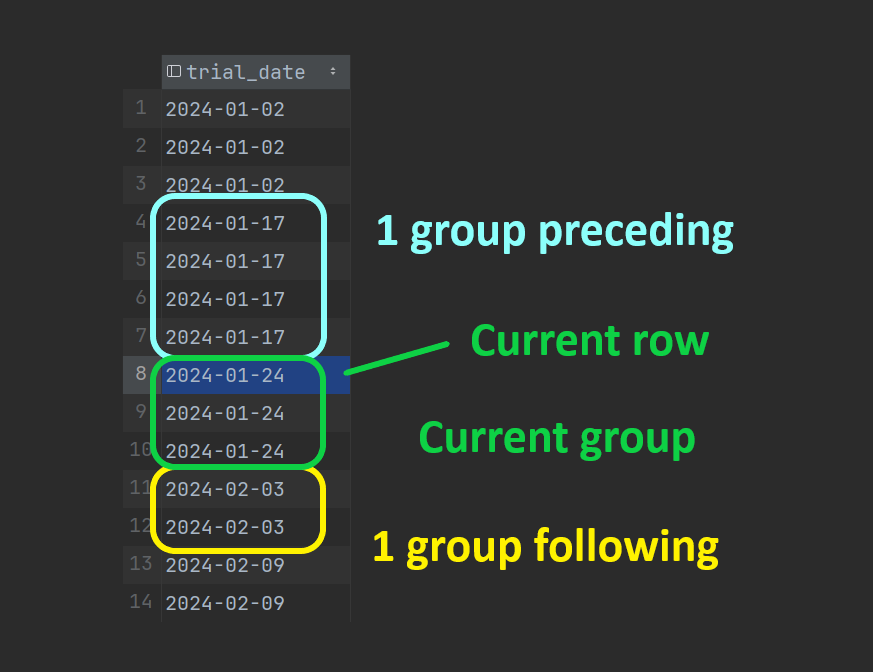

GROUPS query

select

trial_date,

sum(trial_result = 'succeed') over running_trials as succeeded,

sum(trial_result = 'fail') over running_trials as failed

from trials

window running_trials as (

order by trial_date

groups unbounded preceding

)

order by trial_date

GROUPS selected rows

RANGE is a frame type that we like to use, but GROUPS is almost never needed so many database engines don’t even support it.

| Database | Supports RANGE |

Supports GROUPS |

|---|---|---|

| Snowflake | ✅ | ❌ |

| Databricks | ✅ | ❌ |

| BigQuery | ✅ | ❌ |

| SQL Server | ✅ | ❌ |

| ClickHouse | ✅ | ❌ |

| DuckDB | ✅ | ✅ |

| PostgreSQL | ✅ | ✅ |

| SQLite | ✅ | ✅ |

3. EXCLUDE rows in a window frame

Using ROWS/RANGE/GROUPS is great for adding more rows to the window frame, but it’s not uncommon to want to also exclude some rows from the frame.

A few databases support the EXCLUDE option at the end of a window frame precisely for this:

... OVER (

PARTITION BY ...

ORDER BY ...

ROWS | RANGE | GROUPS ...

EXCLUDE ...

)

There are four options for EXCLUDE: NO OTHERS, CURRENT ROW, GROUP, and TIES. The SQLite and PostgreSQL docs do a good job of describing these, which we summarise below. Note that the “peers” of a row are the rows in the same partition that have the same ordering value.

NO OTHERS: The default behaviour — don’t exclude anythingCURRENT ROW: Exclude the current rowGROUP: Exclude the current group (the current row and its peers)TIES: Exclude the row’s peers, but not the current row

For example, if you’re doing anomaly detection, you may want to compare the current row’s value to the average of the values around it: using EXCLUDE CURRENT ROW would allow you to do that in a single window!

select

reading_datetime,

temperature,

avg(temperature) over (

order by reading_datetime

range between interval '1 hour' preceding

and interval '1 hour' following

exclude current row

) as avg_temperature_within_hour_excluding_current_row

from readings

The EXCLUDE option is available in only a handful of databases, including:

4. NULL-safe comparison with IS [NOT] DISTINCT FROM

NULL is the gift that keeps on giving when it comes to bugs in SQL queries.

We all know that we should use = for comparing two non-null values, and IS [NOT] for comparing a nullable value to NULL, but comparing two nullable values has always been a bit fiddly: first check whether they’re both NULL, then whether either are NULL, then finally do the = comparison.

There are some concise implementations, but they’re mostly unintuitive when you first encounter them.

A better alternative is the NULL-safe operator IS [NOT] DISTINCT FROM. This operator will treat NULL as a known value, which leads to far more intuitive results. For example:

1 IS DISTINCT FROM 2→ true1 IS DISTINCT FROM NULL→ trueNULL IS DISTINCT FROM NULL→ falseNULL IS NOT DISTINCT FROM NULL→ true1 IS NOT DISTINCT FROM NULL→ false

It’s a bit more wordy, but using this operator for nullable columns is considerably safer than using just =, and this operator is a better alternative to explicit NULL handling.

Old NULL-safe comparison logic

case

when val_1 is null and val_2 is null

then false

when val_1 is null or val_2 is null

then true

else val_1 != val_2

end as is_different

New NULL-safe comparison

val_1 is distinct from val_2 as is_different

The IS [NOT] DISTINCT FROM operator is part of the SQL standard (from SQL-2023) and is supported in most databases.

5. Expressive join types (SEMI/ANTI, ASOF, LATERAL)

We’ve come a long way since the SQL-92 joins!

The 1992 SQL standard introduced the joins that we’re all familiar with:

CROSSINNERLEFT [OUTER](andRIGHT [OUTER])FULL [OUTER]

Over thirty years later, we’ve found ourselves needing some more expressive joins — particularly in the OLAP world. The implementation of these expressive join types can differ between databases (if they’re supported at all), so make sure you check the docs for your database if you want to use some of these!

SEMI and ANTI joins

The term “semi-join” and “anti-join” have been used for a long time, and have historically been in reference to using a WHERE condition to filter rows based on their existence in another table. Specifically:

- A “semi-join” will keep rows in the base table if their values exist in the referenced table

- An “anti-join” will remove rows in the base table if their values exist in the referenced table

For example, the queries below are both a “semi-join” which keeps customer records for customers that have a “login” event:

select *

from customers

where customer_id in (

select customer_id

from events

where event_name = 'login'

)

select *

from customers

where exists(

select *

from events

where customers.customer_id = events.customer_id

and event_name = 'login'

)

Even though we don’t use the JOIN keyword, we still refer to these as “joins” — and it’s easier to see why in the subquery example on the right.

That said, some databases have explicitly implemented SEMI and ANTI as join types, which would allow the following modern SQL that’s equivalent to the queries above:

select *

from customers

semi join events

on customers.customer_id = events.customer_id

and events.event_name = 'login'

ASOF joins

A common join requirement is “match the record with the same ID that’s the closest to a given timestamp”, commonly referred to as an “as-of” join. For example, matching a financial transaction to the most recent currency exchange rate relative to the transaction time.

Snowflake, ClickHouse, and DuckDB have each implemented this as an explicit ASOF join, but all three have a slightly different syntax for it!

Below is a Snowflake example and a DuckDB example for joining transactional data to exchange rate data using an “as-of” join:

/* Snowflake */

select

transactions.*,

exchange_rates.rate

from transactions

asof join exchange_rates

match_condition (transactions.transaction_ts >= exchange_rates.valid_from)

on transactions.currency_code = exchange_rates.currency_code

and exchange_rates.to_currency = 'GBP'

;

/* DuckDB */

select

transactions.*,

exchange_rates.rate

from transactions

asof left join exchange_rates

on transactions.currency_code = exchange_rates.currency_code

and exchange_rates.to_currency = 'GBP'

and transactions.transaction_ts >= exchange_rates.valid_from

;

If your database doesn’t support these “as-of”, it’s common to use either a lateral join, or a “normal” join which then filters for the closest row using a window function.

Lateral joins

A “lateral join” is just a join on a correlated subquery!*

These aren’t needed very often, but (where supported) they offer a huge amount of flexibility compared to traditional joins. However, they can also come at the cost of significantly degraded performance, so use these with caution.

In most databases that support lateral joins, there are generally two ways they’re written:

select ...

from ...

cross join lateral (

<correlated subquery>

)

select ...

from ...

left join lateral (

<correlated subquery>

) on true

Note that, for the LEFT JOIN version, there is often no join condition outside of the correlated subquery (including it in the subquery is what makes it correlated!), but you can still include additional conditions on the outside if you want — where the database supports it.

Also note that LATERAL isn’t an explicit join type: it’s a keyword specified after JOIN to indicate that the following subquery will be correlated. The CROSS JOIN version acts like an inner join by dropping rows that don’t have a result in the correlated subquery, while the LEFT JOIN version keeps the unmatched rows.

SQL Server also implements lateral joins, but not using the LATERAL keyword — instead, it has the APPLY operator with CROSS and OUTER variants corresponding to the CROSS and LEFT join variants above:

select ...

from ...

cross apply (

<correlated subquery>

) as t

select ...

from ...

outer apply (

<correlated subquery>

) as t

We mentioned a practical usage for lateral join above: implementing an “as-of” join in a database that doesn’t explicitly support the ASOF join type. You can find examples of this HERE.

*There’s some nuance around what counts as a lateral join. In this article, we just consider lateral joins as joining on correlated subqueries.

However, some databases also support a more generalised lateral join which supports joining on (a transformation of) a column in the base table, mainly for unpacking nested values in the column.

We won’t cover these generalised joins here, but examples include:

| Database | Explicit SEMI/ANTI | ASOF | LATERAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Snowflake | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ (limited) |

| Databricks | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| BigQuery | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| SQL Server | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ (APPLY) |

| ClickHouse | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ |

| DuckDB | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| PostgreSQL | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ |

| SQLite | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

One of the Tasman folk has a YouTube series on some of these expressive join types: Bill Wallis: Everything about joints.

Stay tuned for part 2!

The features we’ve covered represent just the beginning of modern SQL’s capabilities. Just as modern data teams are adopting faster development tools across the stack, SQL continues evolving to meet contemporary analytical needs. In Part 2, we’ll explore advanced ways of aggregating data, support for compound data types, and the mysterious recursive CTEs.